PHYSICIAN, PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE OF MEDICINE, EXPERT ON INDUSTRIAL HYGIENE

Situated in the Consecrated/West Section of Jesmond Old Cemetery

Thomas Oliver was born at St. Quivox in Ayrshire, the second son of James Oliver. The young Thomas went to Ayr Academy for his schooling and Glasgow University for his medical training. Having graduated as M.B,C.M. in 1874, he procured a junior post at Glasgow Royal Infirmary and visited Paris for his postgraduate study. He passed the years 1875 – 1879 in practice at Preston before moving to Newcastle to become a Lecturer on physiology at the College of Medicine. He quickly established himself as a Consultant, and was appointed to the staff of the Royal Victoria Infirmary, where he eventually attained the position of Consulting Physician.

His academic career was equally distinguished – in 1911 he exchanged his Lectureship, which had been raised to the status of a Chair in 1889, for the Professorship of Medicine, which he held until 1927. He was President of the College of Medicine from 1926 to 1934 and Vice – Chancellor of Durham University from 1928 to 1930. Additionally, he delivered the Goulstonian Lectures at the Royal College of Physicians in 1891.

Sir Thomas, however, was known best to his profession, both at home and abroad, as an authority on industrial medicine. He was a member of the 1892 White Lead Commission – and, as such, was largely responsible for the banning of female labour in certain processes of its manufacture – and a Home Office expert on dangerous trades, and he took part in many enquiries, public and private, into industrial poisoning. Sir Thomas was the representative of the Home Office at the Madrid International Congress of Hygiene in 1898. In 1902, he edited a valuable survey entitled Dangerous Trades and six years later a work on Diseases of Occupation. His services to public health were recognized by the conferment of a knighthood in 1908 and by several foreign distinctions e.g. the American city of Boston made him an honorary freeman in 1923 and the French Legion of Honour was conferred on him in 1929. In recognition of his research work, he was awarded in 1934 the Hon. Degree of Doctor Danzig University. Sir Thomas was also delegate of the Australian Commonwealth International Labor Conference at the League of Nations in 1921 and Honorary President of the International Congress of Accidents and Industrial Diseases at Geneva ten years later.

The Irish Times, dated Wednesday, July 6, 1910, reports on the Conference of the National Association for the Prevention of Consumption, held in Edinburgh and it quotes Sir Thomas as saying, “statistics showed that a good deal of disease depended upon the occupation followed. If there was one thing which should not be overlooked, it was the potent influence and harm of alcohol.” So, an interesting and potentially controversial causal factor in the acquiring and spread of TB!!

During the 1914 – 1918 War, he helped to raise the Tyneside Scottish Brigade, of which he became Honorary Colonel. The Daily Journal, dated Thursday April 29, 1915, carries a great article that highlights his two roles by focusing on the defects of recruits to the army – some of the language and observations used are quite poignant when viewed through a modern day prism.

Sir Thomas in his Tyneside Scottish uniform.

Sir Thomas says that “between 40,000 and 60,000 men have been given to the Navy and the Army from this district alone. Until the end of December, the Northumberland miners had alone contributed 12,059 men; 31.1 per cent of the men in this district between the ages of 18 and 38 have enlisted. His own experience on the subject upon which he writes has been gained during the raising of the Tyneside Scottish Brigade. Four battalions, each of 1,100 men, have been raised in the short space of 22 days. The recruits have been drawn mostly from the artisan and labouring classes. Only a few of them have been clerks and shop assistants. Most of them have worked in shipyards, iron-works and coal-mines.

It is interesting to see how the previous occupation of the men has helped them as soldiers. Military training, however, soon finds out the weak spots in a man’s body, and this leads me to speak especially of coal miners, who as a class suffer much from fractures of bone in close proximity to their joints. Miners who have followed their avocation for many years, working for the greater part of their shift in a stooping position, become weak in the knees. They suffer very frequently, too, from displaced cartilage of the knee joint. Dr. E. Napier Burnett found that the feet of middle-aged colliers – 40 to 45 years of age – readily gave way during military training owing to pain and thickening of the metatarsal-phalangeal joint of the great toe.

Sir Thomas insists upon the necessity for system and care in the medical examination of recruits, and states that carelessness on the part of medical examiners has been evident in such a large number of instances that by permitting physically defective men to be attested, fed, uniformed, and drilled, who are obliged to be discharged a few days or weeks after attestation, considerable expense has been incurred to the country, disappointment caused to the rejected men, and through them returning home dissatisfied, further recruitment has been made more difficult. It is estimated that the attestation, along with the bonus, the clothing, feeding and subsequent discharge of those unfit for military service, has cost the country nearly £2,000,000.”

An imposing figure at public functions, Sir Thomas was also a most conscientious teacher and physician, noted for setting the example of ‘following up’ cases, and above all for linking physiological principles with clinical medicine.

I came across a great headline in the Washington Post newspaper, dated June 7th, 1926, which reads “Sir Thomas Oliver likes short skirts.” Intrigued by this rather eye-catching statement, the article goes on to clarify by recording that “Reasonably” short skirts and exposed necks and throats have an advocate in Sir Thomas Oliver, President of the London Institute of Hygiene. “When it first became the craze for the greater part of the neck to be exposed, mothers frequently consulted me before giving their daughters permission to abandon high-necked gowns,” said Sir Thomas. At first, I doubted whether it was wise for delicate girls who has repeatedly been treated for winter cough, to try such an experiment. But I soon found that the new fashion banished the winter cough and improved the general health of delicate girls.” Sir Thomas also believes that the growth of women’s hair has been improved by cutting, and shorter skirts have greatly improved health, giving greater freedom of limbs. He also added that “male attire was unattractive, cumbersome and hygienic.”

Perhaps a more famous quote from Sir Thomas arose some seven years later in 1933 when, speaking in Durham, he stated his theory that work is the cure for illness, saying, “People shouldn’t seek the shelter of a do-nothing existence, but take an active interest in life.”

Sir Thomas was Best Man for Lord Armstrong at his marriage in 1935 to a Miss England, daughter of Rev. Charles Thorpe England of Kirkwhelpington. The wedding took place in Rothbury Parish Church with Lord Armstrong being 72 years of age at the time – his new bride was 34.

In relation to Sir Thomas, he married, firstly, in 1881, Edith Rosina, daughter of William Jenkins of Consett Hall, Durham; in the 1881 Census, William is recorded as being the ‘General Manager of Consett Iron Works’ and Thomas is recorded as being a ‘visitor’ at Consett Hall; Edith died in 1888.

Edith Rosina – first wife of Sir Thomas – and Sir Thomas himself, on the front of the monument.

In January 1892, he then married Emma Octavia, daughter of John Woods of Benton Hall, Newcastle, at Long Benton Church – Emma died on 22nd February 1912, aged 58, and is also buried in Jesmond Old Cemetery.

Emma Octavia – second wife of Sir Thomas.

The 1891 Census records Thomas and his young family living at 12 Eldon Square, Newcastle but the time of the 1901 Census, the Oliver family have now moved to 7, Ellison Place, Newcastle, where Sir Thomas lived until his death.

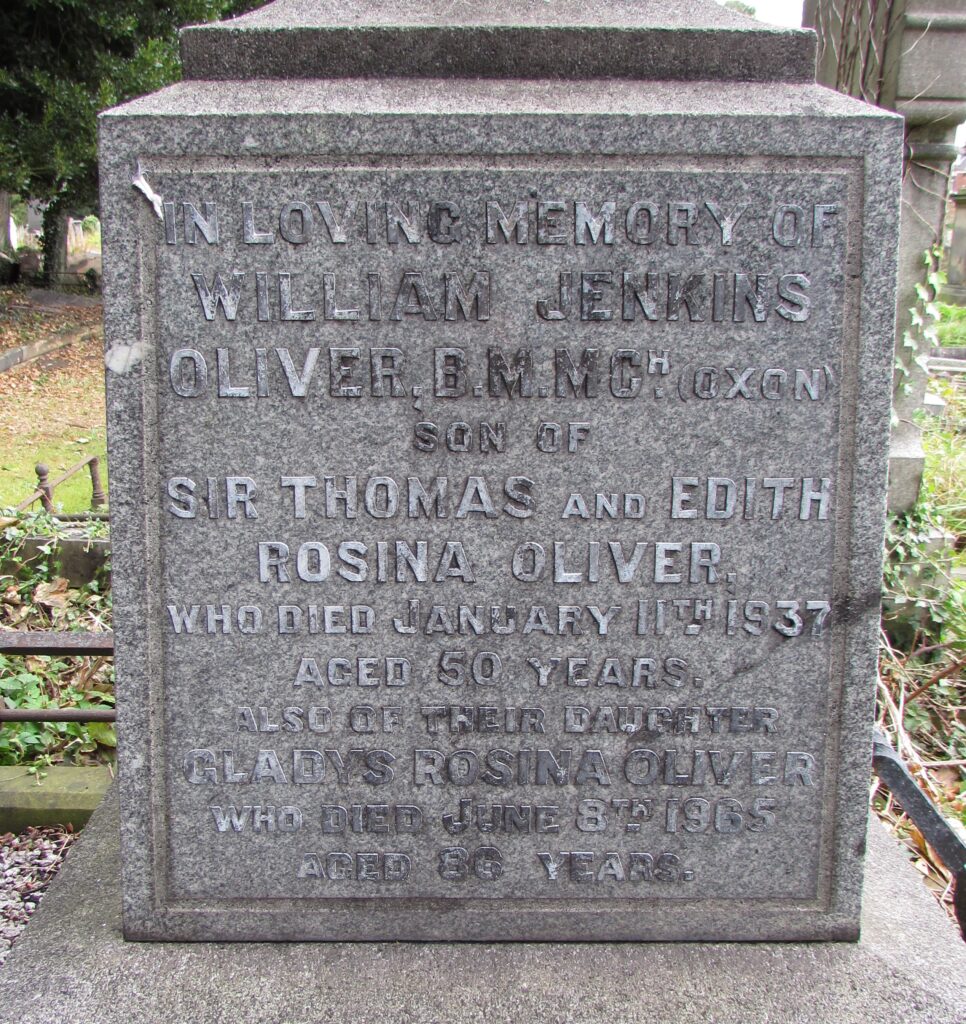

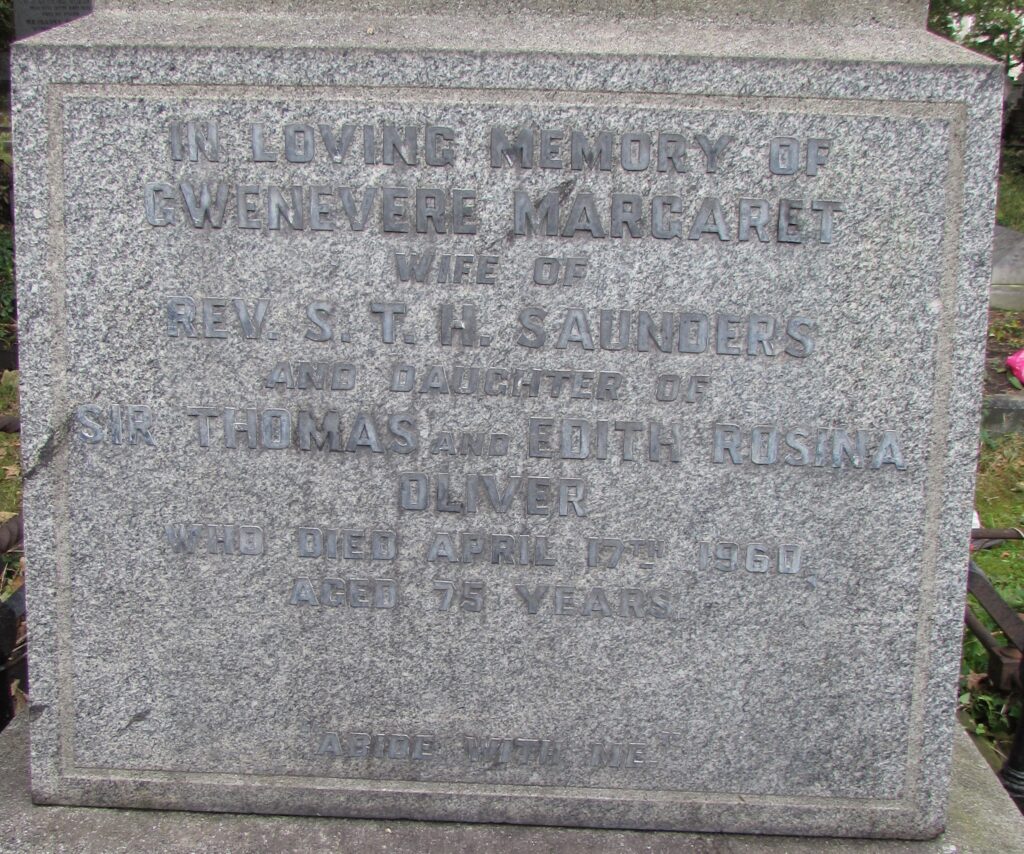

Sir Thomas had two sons, William Jenkins (1886 – 1937) and Frederick Thomas (1897 – 1977). Frederick is mentioned in the Newcastle Daily Chronicle, dated Saturday, February 23, 1918, stating that “Second Lieut. Frederick T. Oliver, Machine Gun Corps, has been wounded in Palestine. He left school to join the O.T.C. and was attached to the Northumberland Fusiliers and afterwards transferred to the Machine Gun Corps.” He also had three daughters, Gladys Rosina (1883 – 1965), Gwenevere Margaret (1885 – 1953) and Kathleen Ellison (1894 – 1976).

William Jenkins and Gladys Rosina.

Gwenevere Margaret.

The Newcastle Daily Journal, dated Monday, September 30, 1918, carries a lovely story about Sir Thomas’ daughter, Kathleen Ellison Oliver marrying Captain Kingsley Dykes, M.C. It encapsulated everything about a ‘high society’ wedding in Newcastle at the time, with the wedding being solemnized at Newcastle Cathedral and had taken place earlier than expected as Captain Dykes had been ordered to take up a special staff appointment with the North Russian Expeditionary Force.

“The bride, who was given away by her father, wore a charming gown, designed and made by Fenwick of Newcastle, of rich cream brocade, made on graceful lines, with a short separate train. The bebe bodice was composed of crepe ninon, with a corsage of silver tissue and high swathed belt of brocade, festooned with narrow silver and cream ribbons. The veil of Honiton lace, lent by the bridegroom’s grandmother, Mrs. Jassmann, was arranged over a fillet of silver ribbon, caught at the back with orange blossom. The Bride carried a bouquet of white roses, lilies of the valley and white heather, this being a gift of Lord and Lady Armstrong of Cragside.

Following the ceremony, a reception was held by Sir Thomas Oliver at the Mansion House, Ellison Place, kindly lent for the occasion by the Lord Mayor of Newcastle. Later, Captain and Mrs. K. Dykes left for Bamburgh, the bride wearing a gown of orchid mauve chiffon velvet and a hat of black panne, relieved with pale yellow beads, again designed and made by Fenwick of Newcastle.”

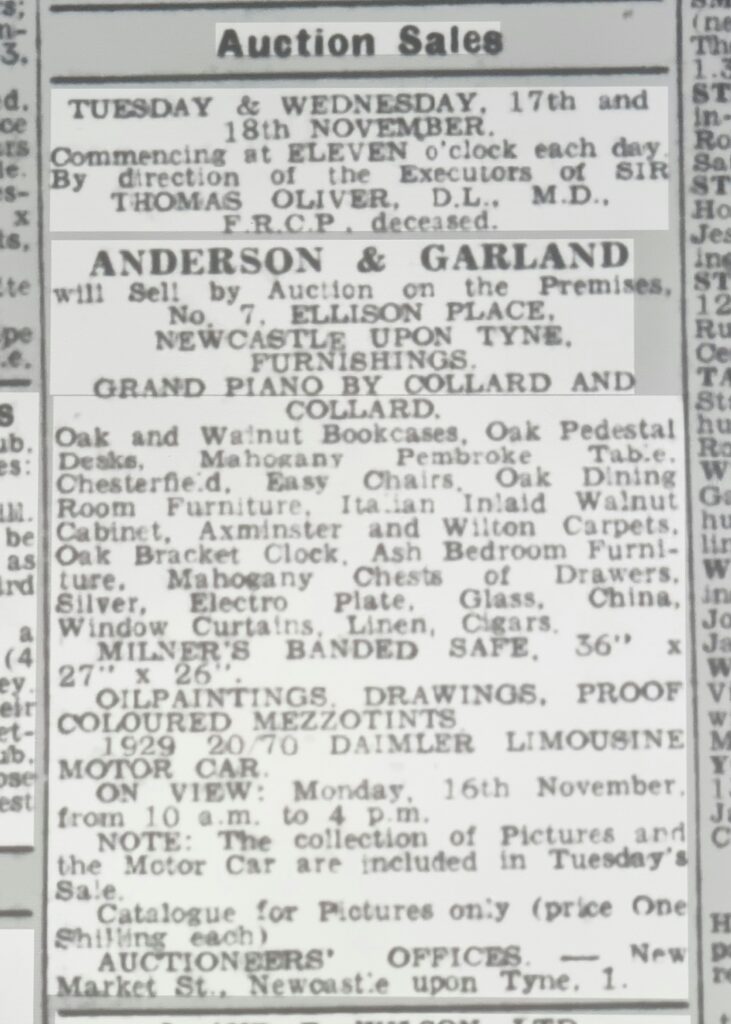

Sir Thomas died, aged 89, on May 15th, 1942. His funeral service, conducted by Canon G.E. Brigstocke and Canon W.H. Alinger, was held at Newcastle Cathedral on May 19th and he was interred in Jesmond Old Cemetery later the same day. Sir Thomas left £91,631 in his will and, amongst the many beneficiaries, including his chauffeur who was left £100, he also left £150 on trust for the purchase of coal for the poor of Ayr.

Advert for auction of house contents following Sir Thomas’s death.

The Blyth News Ashington Post, dated Monday May 18, 1942, carries a lovely story about Sir Thomas, describing how his death, at the advanced age of 89, “brings to an end an interest in the Bedlington district which began on a stormy night soon after the outbreak of the last war when the distinguished physician visited the Terrier Town to find recruits for a brigade of Kitchener’s Army, to be called the Tyneside Scottish, then in process of formation. The response of the Bedlington miners was so overwhelming and created such a deep impression on Sir Thomas’s mind that when the war was over, he prevailed on the authorities to lay up the colours of one of the Tyneside Scottish battalions in Bedlington Parish Church. This signal honour to the men of Bedlington was only one of the ways Sir Thomas took to express his pride in the patriotism and to show his solicitude for the welfare of the mining community.”

The Morpeth Herald, dated Friday, February 7, 1919, gives an earlier account of Sir Thomas’s affection for his Tyneside Scottish soldiers, describing how Sir Thomas “made presentations to four local soldiers from West Sleekburn who have been decorated for services at the Front. Their names are Pte. Simpson who was granted the D.C.M. for conspicuous gallantry in restoring communication under heavy shell fire, having shown magnificent courage and determination. Lance-Corpl. Scott, M.S.M., separated line bombs which were on fire in a box and threw the bombs out of the dugout. There were 60 men in the vicinity at the time, and his prompt and plucky conduct doubtless saved several lives. Signaller J. Easton distinguished himself in the work of laying telephone wire under heavy fire. Lance-Corpl. John J. Black obtained his distinction for a gallant exploit. Two other corporals and a private went to put a gun out of action which was playing havoc with our men. They succeeded in their task, but the other two corporals were killed.

Sir Thomas was pleased to perform that ceremony on behalf of the Tyneside Scottish. He was certain that when the history of the war was written, the deeds of the men of Northumberland and Durham would stand out prominently. As far as trench work was concerned, there were no soldiers in the British Army who had done that work better than the men from the North. When a test was made as to who could do the largest amount of trench work, the miners had done two and a half times more work than even the engineers themselves.”